The Male Gaze Blown Up

Visual Pleasure and Spectatorship in Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up

Pop Culture (LM) — Università di Bologna

Introduction

In Blow-Up (1966), Michelangelo Antonioni presents the story of Thomas, a London fashion photographer, through a form that continuously foregrounds the act of looking. This essay offers a close reading of the film using concepts developed by Laura Mulvey and John Berger, particularly the male gaze, the gendered economy of vision, and the ideological positioning of the camera. Building on feminist readings of the film by scholars such as Gillian Bruno, Ned Rifkin, Jacqueline Rose, and Brunetta, I examine how Blow-Up both enacts and exposes the patriarchal logic of visual pleasure in cinema.

While the film does not critique this logic through overt narrative means, it produces a formal and thematic instability that unsettles the viewer's visual mastery. By examining how Thomas's gaze structures—and ultimately fails to control—the image, I argue that Blow-Up functions as a meta-cinematic meditation on the limits and anxieties of the male gaze.

Men Act, Women Appear

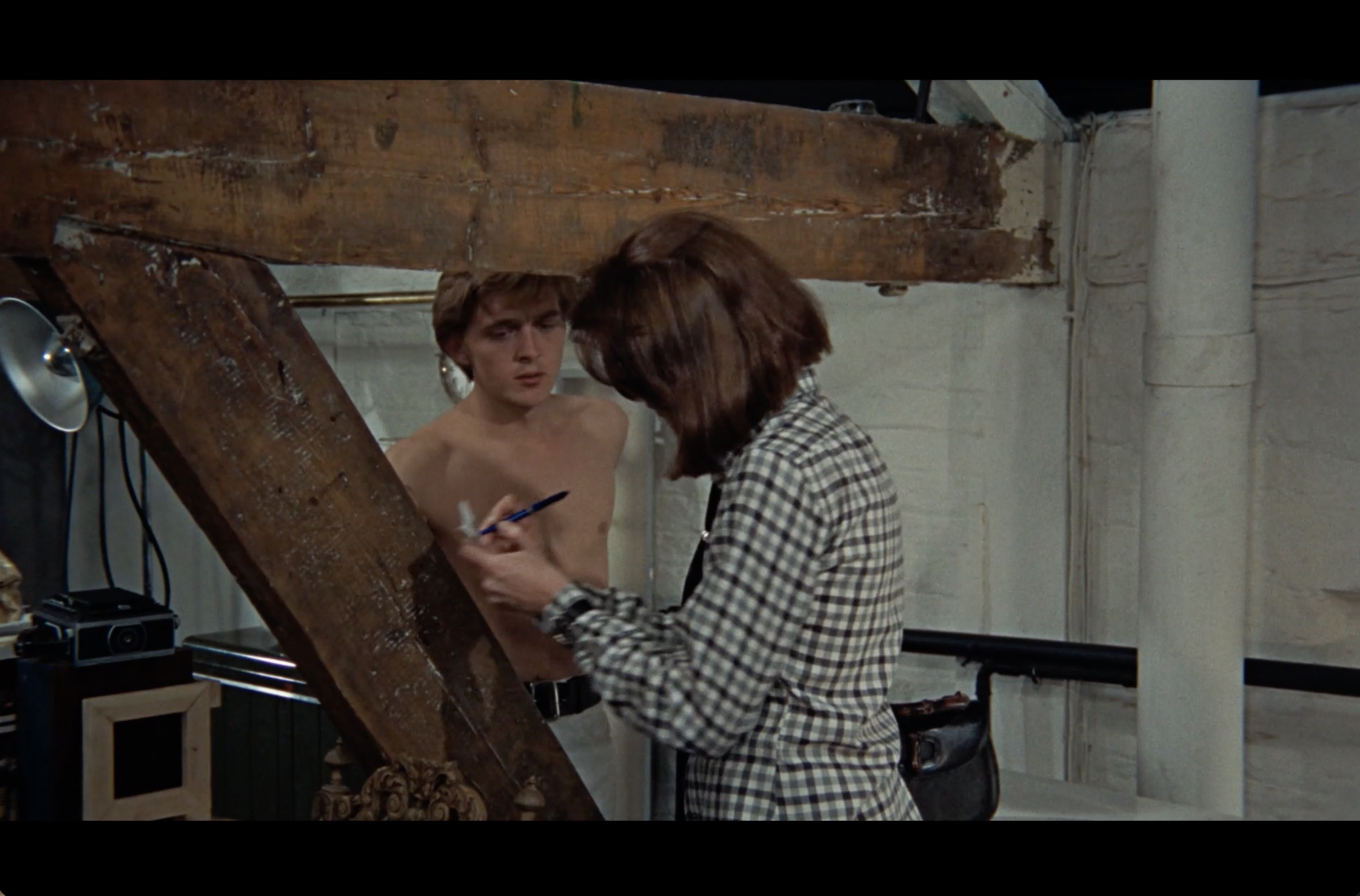

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger argues that "men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at." Blow-Up offers a sustained illustration of this dynamic. Thomas is positioned as an active agent—an artist who roams London in search of visual material—while the women he photographs remain largely objects to be captured and arranged. The opening fashion shoot establishes this pattern: Thomas directs, frames, and poses Veruschka, who becomes a silent, manipulable surface. The scene's framing, in which Thomas is constantly in motion while Veruschka is fixed beneath his lens, reproduces the gendered asymmetry Berger describes.

What distinguishes Antonioni's treatment is its reflexive quality. The camera does not simply adopt Thomas's point of view; it observes him observing. This doubled gaze—Antonioni watching Thomas watching—introduces a degree of critical distance. The viewer is invited to notice the power asymmetry, even if the film does not explicitly condemn it.

Scopophilia, Fetishism, and the Female Form

Laura Mulvey's foundational essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" identifies two primary sources of pleasure in classical cinema: scopophilia, or the pleasure in looking at another as an erotic object, and identification with an idealised image on screen. Both are present in Blow-Up, though in forms that complicate Mulvey's framework.

The film offers multiple instances of scopophilic pleasure: the fashion shoot, the group scene with the aspiring models, the prolonged display of female bodies for the camera. Yet these scenes are marked by a coldness and a formal detachment that undercuts the eroticism. Thomas does not appear to experience desire; his gaze is instrumental, almost clinical. This detachment may suggest the alienated logic of the male gaze taken to an extreme: the woman as image becomes so objectified that even sexual pleasure drains away.

Mulvey also discusses fetishistic scopophilia—the conversion of the female body into a fetish object to disavow the threat of castration. Gillian Bruno applies this framework to Blow-Up, arguing that Thomas's compulsive enlargement of the park photographs represents an attempt to master a disturbing image through fragmentation and scrutiny. If the female body in classical cinema is fetishised to contain male anxiety, then the grainy enlargement—which dissolves into ambiguity rather than resolving into truth—marks the failure of this strategy.

The Gaze Unravels

Jacqueline Rose and Ned Rifkin have noted that Blow-Up stages a crisis of the visual. Thomas's photographs do not yield knowledge; they multiply uncertainty. The more he enlarges, the less he sees. The park sequence, in which Thomas believes he has captured evidence of a crime, ends not in mastery but in epistemological collapse. The image refuses to confirm his interpretation.

This collapse can be read in gendered terms. Thomas's gaze, so confidently wielded in the studio, proves inadequate in the park. The woman he photographs (Vanessa Redgrave) does not submit passively to his lens; she confronts him, demands the film, disrupts his visual authority. Her refusal to be captured without consequence introduces a form of female agency that the earlier scenes deny. Though her motives remain opaque—perhaps criminally so—her resistance marks a limit to the male gaze's power.

Looking at Those Who Look

As Berger notes, the tradition of the nude in European painting typically excludes the spectator's own act of looking from the representation. The woman is displayed, but the viewer is not asked to consider his complicity in that display. Blow-Up reverses this. By making the photographer—and by extension the cinematic apparatus—visible within the image, Antonioni implicates the spectator in the economy of the gaze.

We watch Thomas watch. We see him compose, frame, and manipulate. We are not given the comfortable invisibility of the classical voyeur. This is what Brunetta describes as Antonioni's "riflessione metalinguistica": a turning of the cinematic apparatus upon itself. The film does not simply offer visual pleasure; it exhibits the mechanisms by which such pleasure is produced.

The End of Visual Pleasure

The film's final sequence—in which mimes play tennis with an invisible ball, and Thomas, drawn into the fiction, pretends to see and throw the ball—offers a final dissolution of visual authority. If the male gaze depends on a stable relationship between the viewer and the viewed, this sequence annihilates it. There is no object to see; Thomas's gaze falls on nothing. The soundtrack supplies the sound of a ball that does not exist. Thomas accepts the fiction, and his own image fades from the grass. The surveyor has become, in Berger's terms, the surveyed—and then disappears altogether.

Conclusion

Blow-Up does not dismantle the male gaze in the manner Mulvey calls for; it does not offer an alternative, feminist form of visual pleasure. But it does expose the mechanisms of the gaze with unusual rigour. Through Thomas, the film enacts the patriarchal regime of looking—and through his failure, it reveals the fragility of that regime. The image resists mastery; the woman resists capture; the photographer himself fades into the grain. What remains is a meditation on looking that, while it does not liberate the spectator from the structures of visual pleasure, at least makes those structures visible.

Works Cited

- Antonioni, Michelangelo, dir. Blow-Up. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1966.

- Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books, 1972.

- Bruno, Giuliana. "Towards a Theorization of Film History." Iris 2, no. 2 (1984): 41–56.

- Brunetta, Gian Piero. Cent'anni di cinema italiano. Rome: Laterza, 1991.

- Mulvey, Laura. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 6–18.

- Rifkin, Ned. Antonioni's Visual Language. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1982.

- Rose, Jacqueline. Sexuality in the Field of Vision. London: Verso, 1986.